The War for Cuban Independence

Intro | Before The

War | The War Begins | U.S.

Intervention | After The War |

Sidebars: Frederick

Funston, American Insurrecto | Funston meets Gómez

|

Spanish-Filipino-American War |

An Excerpt from Mark Twain |

A

Poem: "Cuba Libre" | References

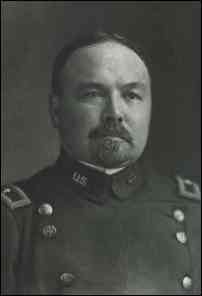

Frederick Funston Remembers the War

An Excerpt from the Book

Memories of Two

Wars

Charles Scribner's Sons, NY, 1911

From chapter 3,

The Fall of Guaimaro, Pg. 62

After the brief but exciting Cascorra campaign, General Maximo Gomez and his force, reduced by casualties and the detaching of various organizations to about one thousand men, infantry, cavalry, and artillery, with two guns, had marched to the eastward, and in a few days was encamped alongside the force of General Calixto Garcia, about two thousand men, that, after a forced march made in obedience to orders from Gomez, had just arrived from east of the Cauto river. We Americans, having learned that General Garcia also had a few guns officered by our countrymen, proceeded to look up these latter without delay, and found several likable and interesting men who were to be our comrades though many months to come. These were Major Winchester Dana Osgood, who had won fame as a foot-ball player at Cornell and the University of Pennsylvania; Captain William Cox, of Philadelphia; Lieutenants Stuart S. Janney and Osmun Latrobe, Jr., of Baltimore, and James Devine, of Texas, and Dr. Harry Danforth, of Milwaukee. All except the latter, who served as a medical officer, belonged to the artillery, with Osgood in command.

As General Garcia, like General Gomez, had but two guns, it will be seen that the artillery of both forces was considerably over-officered. But this fault extended throughout the whole insurgent army, the number of officers, especially those of high rank, being out of all proportion to the number of men in the ranks.

We were soon presented to General Garcia, and were most kindly

received by him. As the future service of the most of us was to be under his

command, and he was one of the most prominent chieftains not only in this war,

but in the ten years' struggle, a few words regarding his personality will not

be amiss. He was a man of most striking appearance, being over six feet tall

and rather heavy, and his hair and large moustache were snow-white. What at

once attracted attention was the hole in his forehead, a souvenir of the Ten

Years' War. On September 3, 1874, being about to fall into the hands of the

Spaniards, and believing his execution to be a certainty, he had fired a

large-calibre revolver upward from beneath his lower jaw, the bullet making its

exit almost in the centre of his forehead. It is safe to say that not one man

in ten thousand would have survived so terrible an injury. He was taken

prisoner, and owed his life to the skill of a Spanish surgeon, though he

remained in prison until the end of the war, four years later. To the day of

his death, nearly twenty-four years later, the wound never entirely healed, and

he always carried a small wad of cotton in the hole in his skull. General

Garcia was a man of the most undoubted personal courage, and was a courteous

and kindly gentleman. His bearing was dignified, but he was one of the most

approachable of men. He seldom smiled, and I never heard him laugh but once,

and that was when on one occasion he fired every one of the six shots in his

revolver at a jutea, a small animal, at a few yards range without disturbing

its slumber. With him life had been one long tragedy of war and prison. He

lived to see his country free from Spanish rule, but not yet a republic. Those

of us Americans who had served under Gomez always regarded him with something

akin to awe or fear, but all who came in close contact with Garcia had for him

a feeling of affection. He was always so just and so considerate, and though

some of us must have exasperated him at times, so far as I know he never gave

one of us a harsh word. When the provocation was sufficient, however, he could

be terribly severe with his own people.

General Garcia's staff consisted of about a dozen young men of the best families of Cuba. All of them spoke English, a great convenience for us foreigners who were constantly under the necessity of communicating with them. The chief of staff was Colonel Mario Menocal, a graduate of Cornell, and a civil engineer by profession. Declining a commission at the beginning of the war, he had entered the ranks, and was with Gomez on his memorable march from eastern Cuba to the very walls of Havana. He was a most capable and daring soldier, and his rise had been rapid. He was the nominee of the Conservative party for the presidency of Cuba at the last election. Another member of the staff was Colonel Carlos Garcia, a son of the general, and the present Cuban minister to the United States. He was a great friend of all of us American mambis, and we usually went to him with such troubles as we had.

General Garcia's force, having been raised in the province of Santiago, had a much larger proportion of negroes than the one that we had been with. With him here were several well-known negro chieftains, among them Rabi and Cebreco, the former one of the most striking-looking men I have ever seen. Some of the negro officers were quite capable in guerilla warfare, while others were mere blusterers and blunderers. Although the color line is drawn in Cuba in social matters, white men of the best families did not hesitate to serve under negro officers, and sometimes on their staffs. The Cuban negroes in the insurgent army were to me a most interesting study. They seemed much more forceful and aggressive than our own colored population as a rule, probably the result of most of the older ones having served in the Ten Years' War. And then, too, they had lived a more out-door life than the majority of the negroes in our Northern States, being plantation hands and small farmers, and had not been weakened and demoralized by city life. A surprising fact was that not a few of the older negroes of Cuba were born in Africa. Although the foreign slave-trade was abolished by law many years ago, it is a matter of common knowledge that up to as late as 1870 small cargoes of slaves from the west coast of Africa were run into Cuba. Juan Gonzalez, the man who served for more than six months as my "striker," or personal servant, told me that he distinctly remembered his capture, when about ten years of age, by Arabs on the Congo, his sale to the Portuguese, and the journey in a sailing-ship across the Atlantic. He ran away from his master and served in the Ten Years' War and so gained his freedom. These African negroes often conversed among themselves in their native dialect, nearly all of them having come from the same region of the Congo.

Note: Usually I make sure that accent marks appear in all the names that require them, such as Gómez. The only reason they don't appear here is that they are not used in the book being quoted. - J.A.Sierra

Related:

Funston Meets Gómez | Funston on Calixto

García, Afro-Cubans in the War of Independence