The War for Cuban Independence

by Jerry A. Sierra

Intro | Before The War | The War Begins | U.S. Intervention | After The War | Sidebars | References

“Once the United States is in Cuba, who will get her

out?”

José Martí

4. After The War

"After more than three years of 'total war,'" wrote Foner in The Spanish-Cuban-American War, Vol. 2, "Cuba lay in ruins. The armies of Spain and Cuba had swept back and forth over the land, carrying ruin with the torch at every trip. What was missed by one army was destroyed by the other."

An American military government was immediately proclaimed in Cuba, with General John R. Brooke as commander. Martí's revolutionary government was never allowed to take control.

On January 1 1899, General Brooke took formal control of Havana from the retiring Spanish governor-general, but the occasion was completely American, and Cubans were denied the long-anticipated satisfaction of parading their troops through the capital. After the Spanish flag was lowered, the U.S. flag was raised.

“Cuba cannot have true moral peace,” wrote General Máximo Gómez in his diary on January 8 1899, “which is what the people need for their happiness and good fortune – under the transitional government. This transitional government was imposed by force by a foreign power and, therefore, is illegitimate and incompatible with the principles that the entire country has been upholding for so long and in the defense of which half of its sons have given their lives and all of its wealth has been consumed.”

In December 1899 General Leonard Wood replaced General Brooke. Along with the military occupation, commercial and business interests invaded the island, assured of every possible cooperation from the new government.

An article in the New York World on July 20 1898,

predicted a new invasion of Cuba following the war. “Whatever may be

decided as to the political future of Cuba,” the article stated,

“it’s industrial and commercial future will be directed by American

enterprise with American capital.” The predictions turned out to be

correct.

The provisional military governments, which controlled Cuban money, refused to provide loans to farmers and landowners to get their crops in shape, using this money instead for roads and sanitation. As a result, American entrepreneurs such as United Fruit Company president Andrew W. Preston, railroad financier Stuyvesant Fish, sugar baron Henry D. Havemeyer and others were able to come in and purchase dirt-cheap farmlands and other properties.

Its widely speculated that the economic and social future of the island would have been more agreeable to Cubans if the military government had followed, instead, a policy of helping the small farmers and planters to resume production.

“This was the legacy of American military occupation,” wrote Foner, “and the refusal to permit the use of the funds belonging to the Cuban people to assist the small farmers and planters to retain their land and rebuild their properties, damaged or destroyed during the Revolution.

…Americans were most ‘energetic’ in picking up land at low prices from people who were without means, and for whom the Occupation government refused to provide loans so that they could develop their property.”

By February 1899, barely six weeks after the formal opening of the Occupation, the process of disposing franchises, railway grants, street line concessions, electric light monopolies and similar privileges in Cuba to foreign syndicates and individual capitalists was about to begin.

The U.S. War Department created a new board for this very purpose, with General Robert P. Kennedy of Ohio as its official leader. The move was opposed by J.B. Foraker, the Senator from Ohio, who introduced legislation (the Foraker Amendment) making these franchises and concessions illegal. This did not, however, "prevent leading American industrialists and financiers from taking over railroads, mines, and sugar properties," wrote Foner, "nor did it stop the military government from aiding them in these ventures." As a result, the sugar and tobacco industries, once controlled by the Spanish, now came to be controlled not by Cubans, but by Americans.

General Wood believed, as did many expansionists in the U.S., that Cuba would, and should, become a state of the Union. Many strong and loud voices advised the U.S. to ignore the Teller Amendment (which prevented the annexation of the island). Editorials in major U.S. newspapers, and the rhetoric of many in the McKinley administration, favored ignoring the law and annexing Cuba. When that option no longer seemed prudent, rumors and articles began to circulate claiming that the Teller Amendment did not apply because the majority of the Cubans wanted to be annexed. But that was just not the case.

“It was clear at all stages of the Occupation,” wrote Foner, “that the annexationists constituted a distinct minority in Cuba. The vast majority of the Cubans insisted on independence. This had been their aspiration for half a century, and for this they had made untold sacrifices. They insisted, too, that the United States live up to its promise. The expression of the will of the majority of the Cuban people doomed the effort in the United States to undo the Teller Amendment. In the end, the annexationists had to concede that their goal was impossible to achieve.”

An editorial in the New York Sun, on April 13 1900, summed up the annexationist point of view. “The attitude of the people of Cuba toward annexation seems to be this in brief; the wealth and intelligence of the island are generally in favor of it, and the agitators and their tools, the ignorant Negroes, are opposed to it.” The editorial went on to suggest that U.S. policy should follow the island’s wealth and sophistication.

Cuba’s first elections took place on June 16 1900. Guided by an electoral law based on U.S. Secretary of War Elihu Root’s plan for a restricted vote, it was deemed that voters must be male, over twenty-one years of age, citizens of Cuba according to the terms of the Treaty of Paris, and they must fulfill at least one of three alternative requirements; be able to read and write; own property worth $250 in U.S. gold; or have served in the Cuban army prior to July 18 1898, with an honorable discharge.

Election results were a resounding defeat for annexationists. The Cuban National Party, made up of the revolutionary element, won the most votes in almost every city, and the Democratic Union Party, which represented Cuban moneyed interests and openly in favor of annexation to the U.S., lost in every election.

The emergent Platt Amendment made a pseudo-colony out of Cuba, imposing a number of conditions that turned Cuban independence into an unfulfilled dream.

“Cuba,” the Platt Amendment proclaimed, “should make no treaty that would impair her sovereignty, she should contract no foreign debt whose interest could not be paid through ordinary revenues after defraying the current expenses of government.” It allowed for U.S. military intervention to “preserve” Cuban independence or the “maintenance of a government adequate for the protection of life, liberty, and property.”

|

|

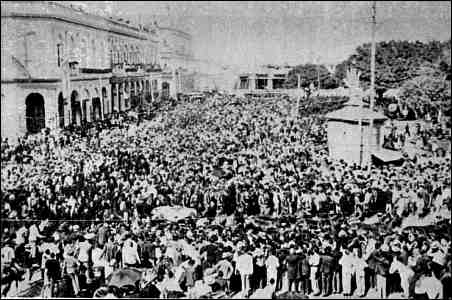

On May 20, 1902, crowds gather in Havana to watch the Cuban flag raised over Morro Castle. |

Cuban leaders were outraged, but the U.S. government would not budge, announcing that the new republic would have to accept the Platt Amendment in order for the military to leave the island. On March 2 1901, the Platt Amendment was incorporated into Cuba’s constitution.

The Cuban flag did not fly over Havana until May 20 1902, when Tomás Estrada Palma was sworn in as the first president of the new Republic.

In 1903, a Permanent Treaty gave the U.S. responsibility for “internal tranquility” and formalized U.S. use of Guantanamo Bay, an issue that remains a sore spot for Cubans to this day.

-end-

Note: In October 1998, one hundred years after the war, Theodore Roosevelt was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Next: Sidebars

Return to Timetable - 1899