The War for Cuban Independence

by Jerry A. Sierra

Intro | Before The War | The War Begins | U.S. Intervention | After The War | Sidebars | References

2. The War Begins

When the war of independence finally began in early 1895, Spanish forces in Cuba numbered about 80,000. Of these, 20,000 were regular Spanish troops, and 60,000 were Spanish and Cuban Volunteers. The “Volunteers” were a locally prepared and assembled force that took care of most of the “guard and police” duties on the island. Wealthy landowners would “volunteer” a number of their slaves to serve in this force, which was under local control and not under official military command.

By December, 98,412 regular troops had been sent to the island, and the number of Volunteers increased to 63,000 men. By the end of 1897, there were 240,000 regulars and 60,000 irregulars on the island.

Numerically speaking, the Mambises didn’t have a prayer.

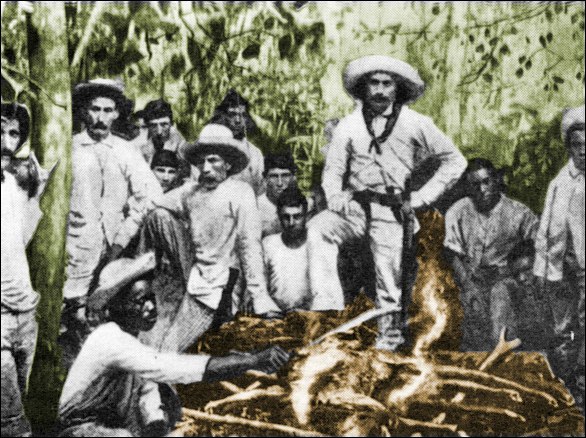

The Mambises

The word “mambises” originated in Santo Domingo, after a brave Negro Spanish officer (Juan Ethninius Mamby) joined the Dominicans in the fight for independence in 1846. The Spanish soldiers referred to the insurgents as “the men of Mamby,” and “mambies.” When Cuba’s first war of independence (known as the Ten Year War) broke out in 1868, some of the same soldiers were assigned to the island, importing what had, by then, become a derogatory Spanish slur.

The Cuban rebels adopted the name with pride.

Weapons and Ammunition

Since the very beginning of the war, one of the most serious problems for the rebels was the acquisition of suitable weapons. Since the end of the Ten-Year War, possession of weapons by private individuals had been prohibited, so the only ones allowed to own weapons were Spaniards and Spanish soldiers, who had the combined benefits of modern weapons and training.

The rebels had no choice but to become effective guerrilla-style warriors using the environment, the element of surprise, a fast horse and a machete. They were often short on weapons and ammunitions, and sometimes the weapons on hand were old, and the ammunition available not suitable.

Most of the weapons used by the Mambises were acquired in raids on the Spaniards. Since Spain controlled the sea, and the mambises had no navy, it became nearly impossible to import weapons from the outside.

Between June 11 1895 and November 30 1897, a total of sixty

expeditions attempted to bring weapons and supplies to the rebels. Of those,

only one succeeded. Twenty-eight attempts were hampered by the U.S. Treasury

Department; 5 were prevented by the U.S. Navy Dept., 4 were interrupted by the

Spanish naval patrol; 2 were wrecked; one was driven back to port by storm; 1

succeeded through the protection of the British; the fate of another is

unknown.

The Death of Martí

On his first battle against the Spanish royalist army at Dos Rios, revolutionary icon José Martí was killed. The rebels tried, in vain, to recover his dead body, but were not able to do so. He was buried by Spanish soldiers on May 27 1895.

Instead of squashing the spirit of revolution, Martí’s death inspired the rebel cause and sent ripples of nationalism throughout the island.

General Martínez Campos and the “trocha”

Credited with the Spanish victory in the Ten Year War, General Martínez Campos expected that the same strategy would help wipe out the rebels in 1895.

The trocha was "a broad belt across the island," about two hundred yards wide and fifty miles long, designed to limit rebel movement to the eastern provinces. Down the center, a single-track military railroad was equipped with armor-clad cars, and various forts and fortified blockhouses were built alongside. A maze of barbed wire was placed so that every twelve yards of posts had 450 yards of barbed-wire fencing. The fortified houses featured loopholes and trenches on the outside, and many encircled windows from which Spanish soldiers could observe and fire.

The eastern trocha ran from Jucaro on the south coast to Moron on the north. "As a final defense," wrote Foner in The Spanish-Cuban-American War, "bombs were placed at points most likely to be attacked, and these had wire attachments to enable their being set off in 'booby trap' fashion."

Because the rebels always managed to have help and information from peasants, they were able to cross the trocha as they pleased.

Maceo in Havana

From the early planning stages the rebels deemed it necessary to bring the war to the Western provinces (Matanzas, Havana and Pinar del Rio) where the island's government and wealth was located. This was an important factor, since the failed Ten Year War had been kept to the eastern provinces by the various "trochas" and concentrated Spanish forces.

The rebels divided their forces into two units; the Liberating Army would remain in the eastern provinces of Oriente and Camagüey, and the Invading Army, headed by Gómez and Maceo (known collectively in the Spanish press as the fox and the lion) would head west.

In ninety days and 78 marches, the Invading army went from Baraguá (at the eastern tip of the island) to Mantua (the western end) traveling a total of 1,696 kilometers and fighting 27 battles against numerically superior forces.

A number of war historians have agreed that the western invasion of Cuba was one of the great military achievements of the 19th century.

Weyler the Butcher

The war was not going well for Spain, and General Martínez Campos was forced to resign in shame during the early days of January 1896. This was a great symbolic victory for the Mambises, since Campos had been credited with the Spanish "victory" in the Ten Year War eighteen years earlier.

Within a few days of Campos' resignation, General Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau (nicknamed the "butcher") was sent to Havana as a replacement.

One of Weyler’s first orders was the fortification of the “trochas.” The modernized “trocha” featured electric lights across the narrow waist of the island from Mariel to Majana, on the border of Havana and Pinar Del Rio. He ordered 14,000 soldiers to be placed in key fortified positions along the “trocha.”

After the new “trocha” was in place, Weyler concentrated his efforts on pursuing Maceo. He sent 3,000 veteran troops, under the command of General Suárez Inclán, to attack Maceo’s forces, which at the time totaled 250 men.

Another tool implemented by Weyler was the system of “re-concentration,” in which various fortified areas were designated, and all inhabitants were given eight days to move in, including cattle and other animals. Anyone caught outside was considered the enemy and killed.

These “re-concentration” towns were very crowded and unhealthy, since Spaniards and soldiers occupied the best accommodations and took the best food. Many died of disease and starvation.

The Death of Maceo

On December 3 1896, Maceo decided that the best way to get around the new, fortified trocha was by water at the port of Mariel. Carlos Soto, a local soldier, was selected to act as a guide, and Maceo handpicked seventeen men to go with him to the East.

Riding with Maceo was Panchito Gómez Toro, (Máximo Gómez' son) who would not be dissuaded, by his father or anyone else, to join Maceo in Pinar del Rio.

It took four trips of a crowded small boat on the following night, at about eleven thirty, to get across, all within sight of a resting Spanish garrison. They took refuge in an abandoned sugar mill called La Merced for two days.

On December 6, frustrated that the horses and supplies that were supposed to greet them had not arrived, Maceo ordered that they start walking. Because of recent leg wounds, Maceo had a very difficult time walking or staying on his feet, although he could fight on a horse as fiercely and bravely as ever. On the road they met the rebel contingent with their horses and supplies, led by Lieutenant Colonel Baldomero Acosta.

That night Maceo decided to join the forces of Colonel Silverio Sánchez Figueras, chief of the Brigade of Southern Havana, at San Pedro de Hernández, near the border of Havana and Pinar del Río. They formulated a new plan to assault the town of Marianao, on the outskirts of Havana.

Resting his wounds on a hammock in San Pedro, as José Miró read from the Crónicas de Guerra (a document describing the war effort) the rebels were surprised by an enemy attack.

Helped to his horse by two men, Maceo pursued the attackers with a machete and a revolver. He leaned towards Miró and said, “Esto va bien!” (This is going well!) A bullet struck him in the face, knocking him off his horse. As the men helped him back on the horse, another bullet struck him in the chest.

The Spaniards did not recognize Maceo's body, nor were they aware that he had joined Figueras' forces, or they would have taken greater care to guard the corpses. That night, a handful of rebels snuck into the Spanish camp recovered Maceo's body.

On December 8 Maceo was buried with Panchito Gómez Toro (Máximo Gomez’ son) at a secret location in Cocahual, at Santiago de Las Vegas.

The war did not end with Maceo's death. Even without the Bronze Titan (as Maceo is remembered) the Mambises were more than the Spaniards could handle. Spain was virtually whipped when the U.S. intervened in 1898.

The War Continues

Since the time of Maceo's death, until April 1898 when the U.S. entered the war, Máximo Gómez had a column of 3,000 men.

The rebels had 41 encounters with the 40,000 Spanish soldiers, cavalry and infantry, stationed south of Las Villas. In various battles, such as the battle of La Reforma, Gómez unquestionably defeated Weyler. The Spaniards were kept on the defensive, and the Mambises initiated every military operation in this area.

One of the most dramatic victories for the Mambises was in Las Tunas, which had been re-named by the Spaniards as Victoria de Las Tunas, in memory of past Spanish victories during the Ten Year War. The town was guarded by over 1,000 well-armed-and-supplied men. On the morning of August 28 1877, General Calixto García gave word to attack. On August 30, Spanish Lieutenant Mediavilla appeared carrying a white flag under orders of Commander Civera to discuss terms of surrender.

“I offered him liberty for himself and his comrades,” wrote Calixto Garcia to Gomez, “the surrender was verified by the turning over of the remaining forts. I have taken more than a thousand rifles and a million bullets. In addition, I have obtained 10 wagon loads of medicine, many machetes, several cannons, and an infinity of cavalry supplies plus supplies of clothing, edibles, etc. The prisoners consist of a chief, two doctors, ten officers, 380 soldiers plus 100 odd non-combatants and volunteers who were armed and fought during the siege.

“I cannot help showing that I am highly satisfied with the conduct of the officers and soldiers who took part in the operations of Las Tunas. I feel true satisfaction in telling you that all of them knew how to stay at their posts with no exception whatsoever.”

It was at about this time that the Philippines declared their independence from Spain, who also faced the possibility of threatened uprising in Puerto Rico. Spain was now fighting two wars—in Cuba and in the Philippines, which further weakened her already unstable economy.

A series of secret dialogues to end the war took place between Spain (who was virtually whipped) and the U.S. (who wanted to purchase Cuba and had, by this time, made various offers that Spain had turned down).

Learning of the secret negotiations, Estrada Palma and other Cuban leaders in New York announced that “only independence and Spanish withdrawal would end the war.”

“We Cubans will never accept autonomy or reform,” said Estrada Palma, “we are fighting for independence and we will accept peace only on the condition of separating completely from Spain.”

In Cuba, Gómez and García issued a statement asserting these very principles and listing twenty facts to prove that Spain had completely failed to crush the rebellion, which was now flourishing better than ever. Among these facts was the election of the Assembly, the siege and capture of Las Tunas by the Liberating Army, the complete civil and military organization maintained by the Republic of Cuba, and more.

"Brutal repression had failed," wrote Foner. "Autonomy had failed. Military strategy had also failed. The strategy of reinforced trochas and concentration camps to deprive the rebels of civilian support and eventually grind them down, had failed.

"On the other hand, Gómez's strategy of making the island economically undesirable for Spain had an overpowering effect. Nearly all economic production was at a standstill, and practically everything of value in the island was devastated."

Weyler was replaced by Don Ramón Blanco y Arenas in October 1897, and sadly for the cause of Cuban independence, the U.S replaced Spain a year later as the official government of the island.

Next: U.S. Intervention

Return to Timetable - 1895