José Martí: Apostle of Cuban Independence

Part

1 | 2 | 3 |

by Jerry A. Sierra

1880S - PRIVATE liFE

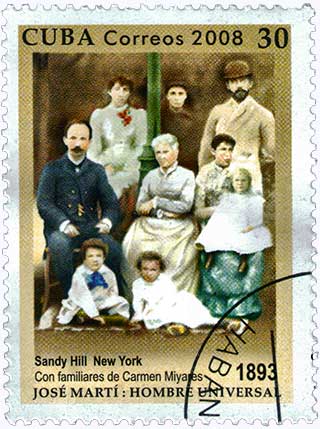

Whatever happened in the Mantilla household between Martí and Carmita since his arrival in New York in January 1880 has been carefully avoided in most historical texts, as is generally the extra-marital lives of other historical Cuban figures.

Manuel Mantilla, Carmita’s husband and father of her 3 earlier children, was a dying invalid, with no known hostility towards Martí. Manuel died in 1885.

As sad as Martí was to be away from his son, he was equally devoted to his daughter of New York, María, and her mother, Carmita.

Martí’s wife, Carmen, did not like anything about life in New York, and stayed in Havana with their son. She visited her husband in New York three times in the 1880s, but could only stay a few months at a time before returning to Cuba. To Martí’s great sadness, his son was raised to support Spanish rule of Cuba. The boy’s grandfather, a Cuban loyal to Spain, gave the boy a watch engraved with the Spanish crest, so that whenever he looked at the time he would be reminded of his Spanish identity.

Most Cuban writers have been very careful not to attack Carmen, although she wasn’t the tough woman that a martyr patriot at that time required. She was very different from other women such as María Cabrales (Antonio Maceo’s wife) or Bernarda Toro (Gómez’ wife) who married men equally dedicated to Cuba’s independence. Carmen would have preferred a less ideological husband, and she expressed her disapproval of Marti turning down lucrative employment so he could work towards Cuban independence.

Most of Marti’s true family life involved Carmita and María, and its clear that he was also a father figure to Carmita’s other children. He educated the girls himself, and encouraged them to become teachers (an acceptable position for a woman at the time) and to speak various languages.

In the book Cuba, author Erna Fergusson describes a conversation in which Señora de Baralt spoke of Carmita. “She was truly a great woman, strong, steady, capable of appreciating what Martí had to do… she gave Martí the tenderness and understanding that his wife could not give him…”

LA liGA DE NEW YORK

In 1890, Martí helped Rafael Serra, a Cuban Negro exile, to found La Liga (The League) an educational center devoted to the advancement of black Cuban exiles. To Martí, the formation of The League represented an important development in the revolutionary movement, since it was a society for poor people, and any Cuban revolution had to base itself on the poor, a theme that would be echoed by Castro and the Cuban revolution of 1959. Besides procuring meeting rooms, obtaining teachers, and helping to increase the membership, he taught a class every Thursday night.

For a while, little María Mantilla became a regular feature of La Liga meetings, playing classical piano and reciting poetry.

In a letter to Serra, Martí says, “And let us never forget that the greater the suffering, the greater the right to justice, and that the prejudices of men and social inequalities cannot prevail over the equality which nature has created.”

Cuban Revolutionary Party

Between 1892 and 1895 Martí devoted himself almost exclusively to the cause of Cuban independence, receiving political and financial support from Cuban exiles in all walks of life and organizing every detail of The Cuban Revolutionary Party. He began to publish “La Patria,” a newspaper devoted to Cuban freedom, and gained notoriety as a dedicated nationalist and fighter for Cuban independence, speaking about the war against Spain as a crusade against evil (much like Castro did in his attacks on the Batista regime and its imperialist ideology).

In a letter to Manuel Mercado, written only days before his death, Martí said that he would gladly sacrifice his life if it would stop U.S. advancement into Hispanic America. In a different letter to Gonzalo de Quesada, dated 10/29/89, he stressed that Cuba must be free of the U.S. as well as Spain, and suggested keeping the U.S. out of the war for independence. "Once the U.S. military is in Cuba,” he questioned, “who will drive it out?”

And yet, writes de Leuchsenring, “the mind of Martí could never conceive of propagating vain and counter producing hatred towards North America. The unique situation of Cuba, geographically and economically, compels the island to friendly and cordial relations with the United States, but without the deadly bonds of political or economic servitude and dependency.” (de Leuchsenring) But this friendship would not be easily established.

“There is no other certain and dignified way to obtain the friendship of the North American people,” Martí wrote to Mercado, “than to excel, before their eyes, in their own capacities and virtues. To flatter the strong and to shrink in his presence is the sure way to deserve the kick of his boot rather than his outstretched hand.” (Foner)

By the end of March 1894, Martí began to push for immediate revolutionary action, writing letters to both Maxímo Gómez and Antonio Maceo. Foner sheds light on his urgency:

“Martí’s impatience to start the revolution for independence was affected by his growing fear that the imperialist forces in the United States would succeed in annexing Cuba before the revolution could liberate the island from Spain. Martí had watched with growing apprehension the diplomacy of Secretary of State James G. Blaine. As Uruguay’s consul in the United States, he had seen at first hand how Blaine used the Pan-American Conference in 1889-1890 to fasten the leadership of the United States upon the Western Hemisphere. He saw, too, that in Blaine’s great design all the Caribbean, all of Central and South America would some day fall to the United States. Cuba was the key to this grand vision because of his strategic location in the Caribbean and its potential as a source of trade and investment. “That rich island,” Blaine wrote on December 1, 1881, “the key to the Gulf of Mexico, and the field for our most extended trade in the Western Hemisphere, is, though in the hands of Spain, a part of the American commercial system… If ever ceasing to be Spanish, Cuba must necessarily become American and not fall under any other European domination.”

Under this scheme of things, there was no room for an independent Cuba. Martí noticed with alarm the movement to annex Hawaii, viewing it as establishing a pattern for Cuba…”

Martí warned Latin Americans not to send their children to study in the U.S., fearing that American wealth would encourage them to cast aside native values and look down on their own people. In one of his most famous observations, he stated that: “Whoever says economic union says political union. The nation that buys, commands. The nation that sells, serves. Commerce must be balanced to assure freedom. The nation eager to die sells to a single nation, and the one eager to save itself sells to more than one.”

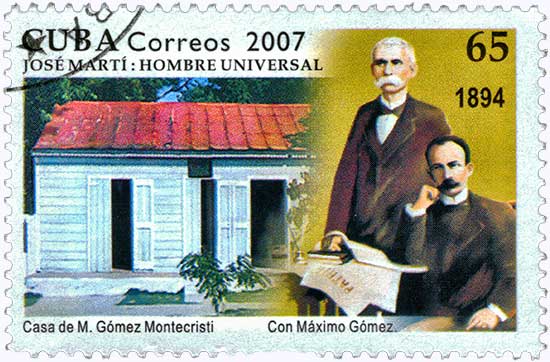

MANIFESTO OF MONTECRISTI

The war of independence started in Cuba on February 24 1895, but Martí and Maximo Gómez were stuck in Montecristi, Santo Domingo, preparing to go to Cuba and join the war. This is where Martí wrote the document known as the Manifesto of Montecristi, a message to the Cuban people, outlining the policy and goals of the Cuban liberation movement. Martí and Gómez signed it on March 25 1895.

The war of independence started in Cuba on February 24 1895, but Martí and Maximo Gómez were stuck in Montecristi, Santo Domingo, preparing to go to Cuba and join the war. This is where Martí wrote the document known as the Manifesto of Montecristi, a message to the Cuban people, outlining the policy and goals of the Cuban liberation movement. Martí and Gómez signed it on March 25 1895.

In this document, Martí paints Cuba as a completely independent republic, free from economic or military control by any outside source. He sees an end to Cuba's one-crop economy and U.S. domination, an end to racial discrimination, and the embrace of Cuba's African population.

The document also outlines what is to be the policy for Cuba's war of independence:

- the war was to be waged by blacks and whites alike;

- participation of all blacks was crucial for victory;

- Spaniards who did not object to the war effort should be spared,

- private rural properties should not be damaged; and

- the revolution should bring new economic life to Cuba.

Martí and Gómez returned to Cuba to participate in the war. They landed on the eastern shore of the island, joining the bands of guerrilla forces that awaited his arrival. (Six decades later, Castro and his followers reenacted Martí’s plan of battle in the very same mountain range, the Sierra Maestra.)

“His ideas formed the foundation on which the revolution rested,” wrote Suchlicki, “and his knocking on the conscience of the Cubans awakened the feeling that brought about the war.” (Suchlicki)

In his book, LA NIÑA DE NEW YORK, José Miguel Oviedo asserts that Marti’s letters to his daughter María in the months before his death may be the maestro’s best work in any genre.

“Love your mother,” he writes to María only weeks before he was killed in battle at Dos Rios. “I’ve never known a better woman in this world. I can’t, nor will I ever, think of her without seeing how clear and beautiful life is. Take great care of this treasure.”

From Cabo Haitiano, on his way to Cuba to join the war for independence, he writes, “when someone is nice to me, or nice to Cuba, I show them your picture. My wish is that you all live together, with your mother, and that you have a good life.”

On his first battle against the Spanish royalist army at Dos Rios, on May 19, Martí was killed. The rebels tried, in vain, to recover his dead body, but were not able to do so.

Spanish soldiers buried Martí's body on May 27, 1895.

from "Simple Verses"By José Martí |

|

|

Cultivo una rosa blanca |

I cultivate a white rose |

|

Y para el cruel que me arranca |

And for the cruel one who tears out |

Martí/Apostle - Part 1 | 2 | 3 | Marti Lives |

José Martí Portal | Timeline | Books | Photos