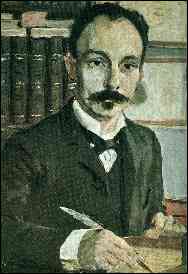

José Martí: Apostle of Cuban Independence

Part

1 | 2 | 3 |

by Jerry A. Sierra

RETURN TO CUBA - 1878

After the Ten-Year War ended in a stalemate that included a pardon to all political prisoners, Martí and his wife were able to return to Cuba, and came to Havana on September 3 1878. Their son José “Pepito” Martí Zayas Bazán was born on November 12 of that same year. Martí was now 25 years old.

The Spanish government, afraid of Martí’s support for Cuban independence, did not allow him to practice law, so he worked as a private school teacher.

Carmen, who came from a wealthy family of hacendados and did not fully agree with Martí’s ideology of separation from Spain, would have preferred for her husband to be just a good father and not Cuba’s apostle of independence.

In 1879, as Martí’s son celebrated his first birthday, Cuban rebels started what is now known as the “Little War.” Martí (who did not support this war) was accused of conspiring with the rebels and deported to Spain. He immediately left for New York and took residence in a boardinghouse owned and operated by Carmen (Carmita) Miyares de Mantilla at 51 East 29th Street, in Manhattan. The house was generally only open to known friends and Cuban exiles known to the revolutionists and independistas, and Martí may have met the Mantillas on previous trips to New York (October 1874 and January 1875).

[This is not far from the 5-Points neighborhood featured in Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York, which takes place about 20 years before Martí arrived.]

1880S - PUBLIC LIFE

Aside from being one of the major figures in the struggle for Cuban independence, Martí is considered one of the great writers of the Hispanic world. “It would require a composite of Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln,” wrote Ramón Eduardo Ruíz in Cuba: the Making of a Revolution, “supplemented by the best of Henry James, Emerson, and Twain to suggest a comparable figure.”

On a snowy January night in 1880, Martí addressed a crowd of Cubans at New York’s Steck Hall. He noticed that blacks tended to congregate at the back of the hall. In Martí: Apostle of Freedom, Jorge Mañach describes how Martí walked on stage and began to speak slowly, “from sententious argument to telling detail and lighting-like metaphor. That clear voice exploded in the air an electric effluvium that dazzled his listeners and took their breath… In revolutionary meetings no language like this had ever been heard.” Martí soon became the unofficial leader of the Cuban independence movement.

During the 1880’s Martí also served as consul for Uruguay, Paraguay, and Argentina, and he wrote for newspapers such as The Hour and The Sun as well as a number of other South American newspapers. He wrote a novel, Amistad Funesta, and two well-received poetry books, including Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) with the famous “I Cultivate A White Rose” (featured at the end of this article).

Martí’s creative output also included Ismaelillo, a book of poems about his son that expressed the deep anguish he felt over their separation. The poems describe a symbolic reunion, which would have meant that Cuba was finally free. Ideas, for Martí, were weapons in the struggle for a better world.

“In all he wrote for some twenty Latin American newspapers,” wrote Kirk, “most of which published his famous Escenas Norteamericanas depicting social conditions and mores of the United States.” (Kirk)

In the introduction to José Martí, Political Parties and Elections in the United States, historian Philip S. Foner wrote that “Martí was the first to reveal to the people of Latin America the methods employed by the great corporations and monopolies of the United States in exercising their control over the country’s political institutions.”

In the time he lived in the U.S., Martí grew very distrustful of Americans, warning that “the white man’s fear of the Negro would impede Cuba’s independence.” In the introduction to a different volume of Martí’s essays titled Our America, Foner writes: “Martí was uncompromising in his defense of black-white unity and equal rights for all. At a time when racist ideas were held by many who moved within the independence movement, Martí showed no hesitation in directly confronting the issue. Of the black man, he wrote: ‘others may fear him; I love him. Anyone who speaks ill of him I disown, and I say to him openly: You lie!’”

The Spanish government frequently predicted that a Cuban revolution would end in a bloody race war, but Martí argued constantly against that point. “A Cuban is more than white,” said Martí, “more than mulatto, more than black… in the daily life of defense, loyalty, brotherhood and attack, at the side of every white man there has always been a Negro.”

The time spent in the slums of New York made Martí increasingly disenchanted with the country’s “casual indifference to human suffering.” “The Gilded Age,” he wrote, “alienates the Cuban, a man who lives from hand to mouth and feels injustice deeply.” His writings of this period alerted Latin Americans to the reality of life in the U.S., and ended the debate of annexation in the minds of most Cuban rebels.

Martí/Apostle - Part 1 | 2 | 3 | Marti Lives |

José Martí Portal | Timeline | Books | Photos