José Martí: Apostle of Cuban Independence

Part 1 |

2 | 3 |

by Jerry A. Sierra

Early Life

Don José Julián Martí y Pérez was born in Havana on January 28 1853. He spent his early years in Spain with his parents, Don Mariano Marti y Navarro and Leonor Pérez, and four younger sisters. Upon returning to Cuba as a boy, he was shocked at the way black slaves were treated on Cuban plantations and felt inclined to voice his opposition.

One of the most important influences in Martí’s early life was his mother, a stern believer in education even though she came, as did his father, from a poor working background. (She’s credited with the now famous quote: “Men are always dissatisfied with whatever government they have.”)

Martí’s father was happy with his smart little boy, and often took him along on his routes as policeman. Little Martí could not only complete his father’s paperwork but he would talk about the issues of the day.

Another significant influence on young Martí was a teacher and poet named Rafael Maria de Mendive, who taught him to express himself through poetry and saw his potential. “In that teacher,” wrote Ferguson, “Martí first met the revolutionary ideas for which he was to live and die.” By age 10 Martí was writing his first poems, and he was a voracious reader, having completed Uncle Tom’s Cabin before his eleventh birthday and expressing concern for slaves and the civil war in the United States.

When Mariano took his son out of school and started him in an apprenticeship as a shopkeeper, Mendive mentored him with a scholarship to the Colegio de San Pablo so young Martí could continue his education. Young Martí was also inspired by learning about Simón Bolívar. (Guerra)

In 1869, less than a year after the start of the Ten-Year War, Martí found his first newspaper, Patria Libre, supporting the rebels and the idea of Cuban autonomy. That same year, Mendive was accused of participating in a rebel rally and exiled to Spain.

Just before Martí reached 17 years of age, authorities found a note he wrote to a schoolmate supporting the revolution and expressing opposition to colonial rule. He was sentenced to six years of hard labor in a military prison, where he suffered a leg injury that forced him to use a cane for the rest of his life. “He worked in a limestone quarry,” explains Jerome R. Adams in Latin American Heroes, Liberators and Patriots from 1500 to the Present.

“His father got Martí transferred to a cigar factory,” wrote Adams, “where conditions were better and prisoners were only fastened to their tables.”

After six months in prison, and through his mother’s influence, the remainder of his sentence was reduced to exile. He was paroled to Don José María de Sarda, a friend of his father, until he left for Spain in January 1871. Later that year a newspaper in Cadiz published 18 year old Martí’s “El Presidio Político en Cuba,” in which he exposed the horrors of political imprisonment.

Martí’s years in Spain were eventful; he continued his education at the Universidad Central de Madrid, and then at the University of Zaragosa, where he received professional certificates in civil and church law, philosophy and letters (similar to subjects Fidel Castro would study seventy years later). And he lived briefly in France, where “…he met Victor Hugo,” wrote Jaime Suchlicki in Caribbean Studies, “whose humanism and love for the poor made a lasting impression…” among others. “Three sons of Spain also had a profound influence on Martí,” wrote Suchlicki. “From Baltasar Gracián, he took his literary style, his liking for philosophical essays for commentaries on ethics and politics; from Francisco de Goya, kindliness toward the humble and the penetration that unveiled men’s souls; from his contemporary, Joaquín Costa, his love for agriculture, his friendliness for rural workers and his uncompromising repugnance for the evils of politics or expedient dissimulation.”

Martí moved to Mexico in 1875, and upon reuniting with his family he learned that his sister Ana had just died. But otherwise he fared well in Mexico, where “political and literary climates were perfect for him” (Adams) and his articles for Revista Universal, under the pen name Orestes “won him immediate acceptance in Mexican literary society.”

His play, “Amor con Amor se Paga” (Love Is Repaid by Love) written for the Spanish actress Concha Padilla was a success.

Using his second name, Julián, and his mother’s maiden name, Pérez, he smuggled himself into Cuba in early 1877 without being identified. But unable to work, and aware that the cause of Cuban independence was lost for the time being, he returned to Mexico after a month, and then to Guatemala, where he taught history and literature at the Nomal School from March 1877 to July 1878. (Foner)

Martí’s personality was described as eclectic, borrowing from a multitude of sources, and he was a voracious reader with many interests and ideas. He loved Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, whom he called the poet of the people.

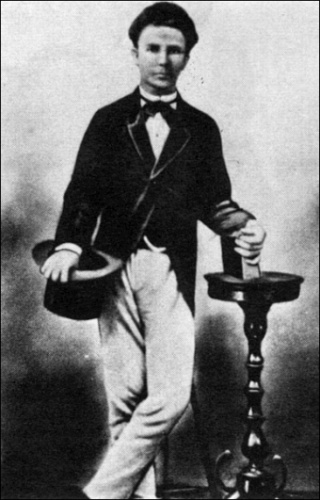

He was a thin man, not taller than five-and-a-half feet, with a high forehead and intense, penetrating eyes. He usually wore dark suits with white shirts and dark bow ties, which he purchased second hand, but friends joked about how clean his clothes always were.

On December 20 1877 Martí married Carmen Zayas Bazán y Hidalgo, the daughter of a wealthy Cuban exile.

Martí/Apostle - Part 1 | 2 | 3 | Marti Lives |

José Martí Portal | Timeline | Books | Photos