Race War of 1912

"The 'race war' of 1912 was, in reality, an outburst of white racism against Afro-Cubans." - Aline Helg in "Our Rightful Share, The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912"

At the end of the 2nd War for Independence, the prospect of peace and self-determination filled Afro-Cubans with a hope they had never been able to experience. They felt they had earned the rewards of a free society, and the very idea of self-government implied a free, integrated society with equal access to schools and business opportunities. This is what Martí and Maceo had promised. This is what 86,000 Afro-Cubans had died for in the War of Independence (1895-98).

"Peace changed everything," wrote Louis A. Pérez, Jr. in The Hispanic American Historical Review. "Gains made during the war were annulled. The expatriate juntas disbanded. The provisional government dissolved, and the Liberation Army demobilized. Suddenly, all the institutional expressions of Cuba Libre in which Afro-Cubans had registered important gains disappeared, and with them the political positions, military ranks, and public offices held by thousands of blacks."

The Partido Independiente de Color, established in 1908 by Evaristo Estenoz and others, sought to correct the problems of the new republic, but found itself unable to push its agenda forward. The Morúa Law of 1909 banned political parties based on race or class, and even the government of liberal José Miguel Gómez had limited sympathy for their issues.

One of these issues was the Morúa Law, which would not allow independents to run a candidate for president. Another issue was the ban limiting immigration by Haitians and Jamaicans.

In 1910, leaders of the Partido Independiente de Color had been arrested and charged with conspiracy against the Cuban government. After a trial they were all found not guilty.

In order to protest the failure of the new republic to adhere to Marti's vision, and to call an end to the Morúa Law, the Partido Independiente de Color planned a demonstration for May 20 1912. Demonstrators chanted "Down with the Morúa Law! Long Live Gomez!" and there was no violence. The demonstration was quickly misrepresented as racist against whites, causing a great deal of panic and reviving old fears.

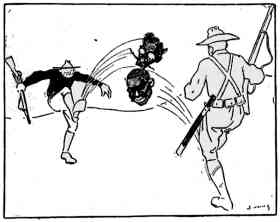

"At the first sign of an Independiente show of force," wrote Helg, "the Cuban political elite labeled the movement as a race war that the Partido Independiente de Color had allegedly launched against the island's whites. Mainstream newspapers were particularly eager to propagate this view of the armed protest."

Newspapers reported the demonstration as a race war, arousing great fear among white Cubans. Publications such as El Día, La Discusión, La Prensa, El Triunfo, El Mundo, and others, ran with the "race" idea, stirring the traditional race fears of white Cuban society.

Reports of Afro-Cuban rapes of white women, including a teacher (none of which were true) and exaggerated accounts of the demonstrations, inspired white militias to form all over the island, and the "race war" became the main topic of conversation.

On May 26, the newspaper El Día, reported;

"This

is a racist uprising, an uprising of blacks, in other words, an enormous

danger… Such uprisings are moved by hatred, and their purpose is negative,

perverse; they are only conceived by something as black as hatred. They do not

try to win but to hurt, to destroy, to harm, and they do not have any purpose.

And they follow the natural bent of all armed people without aim and driven by

atavistic, brutal instincts and passions: they devote themselves to robbery,

pillage, murder, and rape. These are, in all parts and latitudes of the world,

the characteristics of race struggles.

"Racial uprisings are naturally cursed; they are the cry, the voice of barbarism. And everywhere, the voice of the guns, which is the voice of civilization, answers and has to answer them.

"And this is the kind of movement, of activity that one can see in all the Cuban country: civilization is arming itself against barbarism and is getting ready to defend itself against barbarism.

"This is the free and beautiful America defending herself against a clawing scratch from Africa."

Other publications carried the racist themes even further, exploiting deeply rooted racist ideas from the Spanish empire, and brushing up on newly acquired racist rhetoric. Exaggerated and downright inaccurate reports of black attacks on whites, murders and rapes, were everywhere. Later reports would prove them all completely wrong.

Another sad and interesting aspect of public reaction is that newspaper reports and government rhetoric assumed and implied that skin color alone determined your side in the conflict. It was a known fact that many Afro-Cubans did not agree with the Partido Independiente de Color, nor were they members of the party or participants in the demonstrations. Yet the old fears prevailed.

All over the island, Afro-Cubans were arrested, harassed, and killed, simply out of "suspicion." Suddenly, in May and June of 1912, it was very dangerous to be of dark skin in Cuba. Men and women were attacked by militias as they were walking home from work, or visiting with friends. There was a great deal of suspicion that all Afro-Cubans were secretly involved in the "race war."

On May 23, police near Cienfuegos shot to death 8 "peaceful negroes." Black skin was enough reason to suspect a person, and suspicion seemed to be enough reason for execution. At this time, the protesters had not destroyed any property.

Generoso Campos Marquetti, a member of the House of Representatives, tried to prevent the massacre by proposing amnesty (on May 26) for rebels who surrendered within ten days. His motion was ignored, and Congress supported the President's policy of repression in Oriente with a resolution on May 27.

Throughout the island, Afro-Cubans were detained, harassed and murdered. Groups of young men going home after the zafra, and even people who had not participated in the demonstrations but were trying to avoid being seen, were deemed suspicious and arrested or killed. There were no consequences for "protecting civilization."

The massacre continued into June. In Boquerón, near Guantánamo Bay, a captain and five volunteers beheaded a policeman and stabbed to death five others who had been arrested on an unsubstantiated charge of conspiring with Jamaicans to aid the rebels. On June 10 the U.S. consul filed a report stating that "many innocent and defenseless negroes in the country are being butchered."

Bodies of suspected "rebels" were left hanging outside the towns for "moral reasons," and severed heads were placed on the side of the railroad tracks so train passengers could see them.

Several Afro-Cuban veteran offices were arrested in early June (General Juan Eligio Ducasse, Colonel Jose Galvez) even though they were neither members of the Partido Independiente de Color, nor did they support the rebels. Their only crime was to question the wisdom of racist violence and the concept of "race war" being nurtured. They were later released for lack of evidence.

Other Afro-Cuban veterans of the War of Independence, such as Jesús Rabí and Florencio Salcedo, also protested the fact that all troops sent to Oriente were under the rule of white officers.

Estenoz and Ivonnet were shocked at the outbreak of violence. The independents divided themselves into various small groups and took to the mountains and forests of Southern Oriente, where they would not be easily found. They robbed some "estate shops," and avoided confrontation with the army or rural guards.

In the cities, theories of black conspiracies were everywhere. One popular conspiracy theory involved a plot by Haitians and Jamaicans to take over the country, another involved conservatives seeking U.S. annexation. None had any basis in reality, but added immensely to the fear and confusion of the time.

In order to put a quick end to the situation, and avoid another US military intervention, President Gómez allowed the reinstitution of concentration camps in Oriente province. Families were forced into these camps by the thousands, clearing out the countryside so that anyone found roaming about was deemed an enemy combatant and "eliminated." (Similar measures were used by Spanish General Valeriano Weyler against the Cubans in 1896.)

On May 31, the independents attempted to show their determination with a "limited sabotage" in Oriente. They burned a bridge, a post office, and the barracks of a rural guard, some wooden houses that belonged to the Santa Cecilia Sugar Company, and a railway station. On June 1 they took control of the town La Maya, where Afro-Cubans were a majority, and burned down some houses. There were no casualties or injuries.

In Santa Clara, independents formed two fugitive bands with a total of about 50 men. The government sent 3,000 well-armed soldiers and volunteers to deal with them.

"The movement was crushed immediately everywhere except in Oriente, especially Guantánamo region," wrote Hugh Thomas in Cuba, or The Pursuit of Freedom. "The alarm was nevertheless immense, Havana being overwhelmed by panic. Everyone had feared a 'Negro uprising' for years. The atmosphere resembled the 'Great Fear' in the French Revolution."

The methods of elimination were as brutal and barbaric as any ever seen on the island. Decapitated bodies were left on the roadside, and Afro-Cubans who tried to turn themselves into the authorities were killed "trying to escape."

Louis A. Pérez, Jr. explained; "What occurred in eastern Cuba in 1912 was only marginally related to the armed movement organized by the Partido Independiente de Color. The Independiente protest set in motion a larger protest. The political spark ignited the social conflagration, and the countryside was set ablaze. Disorders quickly assumed the proportions of a peasant jacquerie: an outburst of rage and the release of a powerful destructive fury directed generally at the sources and symbols of oppression. As is often the case with peasant movements, the uprising possessed a formless and desultory character. It was a popular outburst, born of social distress and directed not at government but at local social groups and specific conditions of abuse. It was without a program of reform, without a commitment to a unifying program, without organization, without defined policy, and without formal leadership. The protest gave expression to collective rage, and for all its spontaneity and ambiguity, it was not without method and meaning. As an outcry against injustice, it sought at once to destroy the dispossessors and expel the expropriators in one surge of violence and destruction. The protesters attacked property, they plundered and pillaged mostly foreign property, and mostly sugar property, and together these activities served to define the essential character of the uprising. The yearning for the old ways served as the source for the destruction of the new ones.

"These were veterans of the war of liberation: they had once before waged war with fire. Arson was a weapon of rural protest long familiar to the farmers and peasants of Oriente."

About 10,000 Afro-Cubans participated in the "uprising" which never involved confronting people. Not once did protesters engage civilians or government troops in combat.

It's impossible to tell exactly how many Afro-Cubans died. "Official Cuban sources put the number of dead rebels at more than 2,000," wrote Helg. "U.S. Citizens living in Oriente estimated it at 5,000 to 6,000. In contrast, the official figure for the total dead in the armed forces was sixteen, including eight Afro-Cubans murdered by their white mates and some men shot by friendly fire."

The few militiamen charged with any crimes were pardoned, and most of the atrocities were not investigated.

"An appraisal of the destruction is also impossible to make," adds Helg, "because many damages ascribed to the independientes were exaggerated or fabricated by journalists and government officials as a means of antiblack propaganda."

The various volunteer militias roaming the Oriente countryside looking to engage independents added their share of damage, appropriating properties, horses and livestock, and causing their share of property damage. "The British and French consuls in Santiago de Cuba feared voluntarios and marauders more than rebels," wrote Helg.

Evaristo Estenoz, one of the leaders of the Partido Independiente de Color, was shot at point blank range and killed on June 27. Pedro Ivonnet gave himself up on July 18, but was killed the same day "trying to escape."

It was alleged that a secret agreement had existed between President Gómez, Ivonnet and Estenoz, in which the President would intervene to end the demonstrations and the Morúa Law would be abolished. The Partido Independiente de Color would then throw its support behind a 2nd term for President Gómez. If such an agreement existed, it has never been proved. The papers and personal effects of Ivonnet and Estenoz were never recovered.

Whatever myth existed about racial equality in Cuba was shattered in May and June 1912. Not only was there no significant cry of outrage about the massacre from white Cubans, but the majority of newspaper accounts and editorials expressed a kind of racism not seen in Cuba since immediately after the abolition of slavery in 1886.

Editorials pointed out that in Cuba "one of two (opposed races) forcibly has to succumb or to submit: to pretend that both live together united by bonds of brotherly sentiment is to aspire to the impossible." Others recommended that Cuba be "ruled by a small white elite, through a system of plural vote that overrepresented the upper class, and that blacks' access to politics and public jobs be limited because of their 'lesser preparation.' And yet others suggested looking to the U.S. for a blueprint on "race relations."

- -

"This massacre achieved what Morúa's amendment and the trial against the party in 1910 had been unable to do," wrote Helg, "it put a definitive end to the Partido Independiente de Color and made clear to all Afro-Cubans that any further attempt to challenge the social order would be crushed with bloodshed."

Race in Cuba

Opening | Introduction | End of

Slavery | Race Fear |

After the War |

SUGAR | Race

War | Race War Timeline |

José Miguel

Gómez | Morúa Delgado

| Fernando Ortíz |

Julián Valdés Sierra |

Oriente Province |

Martí on Race |

Bibliography

Return to 1912