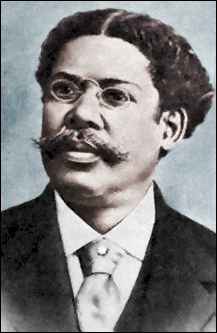

Juan Gualberto Gomez

On July 12 1854, Juan Gualberto Gómez was born the free child of mulatto slaves in Sabanilla de Encomendador, Matanzas. Under existing Spanish colonial law (vientre libre), his parents, Fermín Gómez and Serafina Ferrer, were able to purchase their unborn child's freedom. (They later bought their own freedom.)

When he was old enough, his parents sent him to France to be educated as a carriage maker, an acceptable profession for a black Cuban. The French teacher noticed something unusual about the young Gómez, and he convinced his parents to apply their savings towards a formal education.

After the end of the Ten-Year War, Gómez returned to Cuba and found La Fraternidad, a newspaper dedicated to racial harmony, liberty and social progress for la raza de color.

In March 1880, during the Little War (La Guerra Chiquita) Gómez was arrested for supporting the Cuban rebels, and deported, as had been José Martí sometime earlier.

Gómez spent two years in a Spanish prison in Ceuta, Morocco, and was exiled to Madrid for 8 additional years, unable to return to Cuba. He continued contributing articles and letters to La Fraternidad during this absence, and was finally allowed to return home in 1890.

While in Spain, he wrote for the newspaper El Abolicionista (The Abolitionist), and became the Secretary of the Abolitionist Society of Madrid. He also worked with Spanish lawyer Rafael Maria de Labra to end the practice of Patronato*, while working as a parliamentary reporter for various Spanish newspapers.

Using the legal knowledge he'd acquired in the Spanish parliament, Gómez published a series of articles that challenged current ideas about the colonial relationship between Cuba and Spain. He attacked the established notion of black inferiority in an article called "To a Prejudiced Person" (La Igualdad, December 19 1893). He noted that most of those who discriminate were taught this behavior. "How could the color of black skin produce repulsion in you," he wrote, "when the black nanny was probably the person that your eyes contemplated with greatest affection when they began to see?" The concept of superiority and inferiority, he claimed, is artificial.

Gómez made an example of his self-sacrifice by staying on the island and facing down his opponents through the legal system. His victory would be shared with all Cubans.

Gómez went on to write the controversial "Why We Are Separatists" (Por qué Somos Separatistas), which outlined the reasons why Cuba had to separate from Spain. Using his knowledge of the law, he tried to empower black Cubans, and frequently pointed out how existing laws were selectively abused and/or ignored in Cuba. This article leads to his arrest without bail in 1891, and to his detention for 8 months. It wasn't until his friend Rafael Maria de Labra argued his case before the Spanish Supreme Court (Nov. 21 1891) that he was released.

The high profile nature of this case had profound consequences on Cuban society, and lead to numerous new "separatist" publications on the island.

Instead of escaping to the U.S. (as many advised him to do) Gómez made an example of his self-sacrifice by staying on the island and facing down his opponents through the legal system. His victory would be shared with all Cubans.

Later, as President of the Directorio Central de las Sociedades de la Raza de Color, he neglected the tendency to distinguish between blacks and mulattos. A weeklong convention organized by Gómez (July 23-27, 1892), was attended by 100 societies from all over the island represented by the Directorio. Gómez spoke of the "hombre sin adjetivo" (man without adjective).

Both Antonio Maceo and José Martí made similar arguments, hoping that racial fears would not impede the progress of the Cuban revolution. They agreed that recognizing Afro-Cuban human rights in the legal system was an important step in the evolution of Cuban society, but didn't always agree with Gómez' insistence on separate/stated rights for black Cubans.

During the War of Independence (1895-1898), Gómez rose to the rank of General, and after the war he continued his work, opposing the Platt Amendment and insisting on an independent Cuba. He died in 1933.

The Association of Reporters of Havana, and the Union of Journalists of Cuba named their highest prizes after him, and the airport in Matanzas is named after him.

*Patronato was an apprentice system instituted after the Ten-Year War (1878) in which slaves would be paid an annual salary, but would still be obliged to live and work on the plantation under the "patronage" of their former master. El patronato was conceived as a gradual, indemnified abolition of slavery, which eventually ended in July 1886. In practice, however, this was not a realistic system to end slavery, as some slaves ended up "owing" their former masters.

Related:

José Martí | The war for

independence, aka the Spanish-Cuban-American War